Easter Egg Hunting In The Great African Seaforest

Faine Loubser

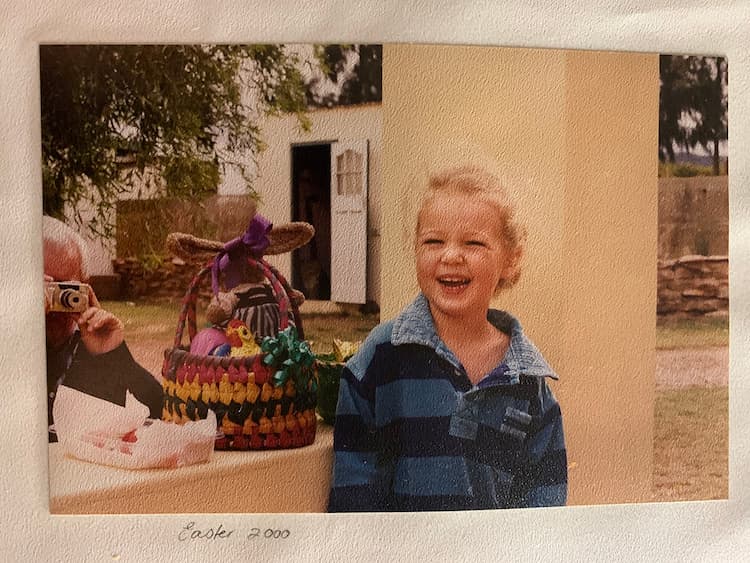

As a young girl, Easter was a time filled with much excitement fueled by the promise of chocolate and heightened by the allure of hunting for treasure hidden by a mystical rabbit.

I grew up on a farm, so naturally, the possibilities for egg-hiding were endless, to the point that I sometimes found eggs a few days after the initial hunt. As I grew older and wiser, it became apparent that the Easter Bunny was particularly tall, perhaps even as tall as my Dad, who’d often have to help pluck the eggs from a tree 2 meters up — although, any suspicions faded in the face of my acceptance of the great, mystical unknowns. Who says there isn’t a 2 meter rabbit hopping around with chocolate eggs? Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Nowadays, I spend my time very differently: Swimming through an underwater forest tracking down elusive cuttlefish eggs, assessing predatory marks in shells and trying to ascertain the particular species of some strange and curious egg casing — adult stuff. If the farm felt big to little 5-year-old me, the kelp forest feels cosmic in scale, and finding the eggs hidden by my pare… I mean, the Easter Bunny would be the equivalent of hunting for bright orange traffic cones, in comparison to the cryptic lifeforms of the Great African Seaforest.

In this environment, predators are everywhere, which accounts for the ingenious measures these creatures have undertaken in order to ensure their species’ survival. The common octopus is a fantastic example. In all of my years (in fairness, only four), I have not once seen the eggs of these animals. The female lays them at the back of her den. She then seals herself inside and awaits her own demise, using all of her energy to oxygenate and guard the growing octo-babies in an ultimate form of self-sacrifice, or perhaps (depending on the level of consciousness one credits to octopods) the greater knowledge that the death of one thing can be the flowering of a new thing.

Just few meters away, hidden in nearby sargassum (seaweed), a future octopus predator lurks, in the form of a striped catshark foetus. These are one of several shark species in the kelp forest which are oviparous (egg layers). For up to 8 months, these little shark babies are incubated in a strong egg casing, and during this time they continuously wriggle around, maintaining a fresh flow of oxygen inside their egg. Apart from the substrate to which they are laid, and the protection of the egg casing, these sharks are super vulnerable, often predated on by whelks, starfish, otters and even baboons in the intertidal zone. It’s a pretty tough start to their lives, but to increase their chances of survival, they have one trick up their fins. These little shark babies engage in a fascinating threat response known as playing possum. Essentially, upon the detection of an electrical impulse, be it movement or light, these sharks immediately stop all movement inside their egg (the shark equivalent of holding one’s breath) and “play dead”. This reduces their own release of electrical impulses and mitigates the spread of odour cues for predators that rely on smell.