Whale Medicine

Jannes Landschoff

“The world stops as I look into his huge black eye. As he comes closer I stretch out my hand, a single touch with my fingertips on his smooth rubbery soft skin electrifies my life.”

The ocean and the organisms living in it have always been my biggest fascination. As a child I spent every possible minute outside chasing small creatures. Growing up in Germany this was the aspect of nature available to me. There were few large animals, and to see something as big as a whale was something I could not even dream of. To me as a kid, whales were dusty bones in the museums; the living creature was more part of my imagination than real. In European waters, my ancestors had driven all living examples to near-extinction.

My passion for nature nurtured me to become a marine biologist specialising in biodiversity research. Besides studying crabs, I of course learned over time that whales are still pretty real. The return of the whales over the last decades may be the greatest conservation story of our times. Today I live in Cape Town where these magnificent creatures can be seen regularly. And as the largest animals that have ever lived on this planet, they still hold mystery and fascination for me.

It was during my postgraduate research at the University of Cape Town when the irony of my emerging disconnection from nature crept slowly into my being. It felt like the harder I worked on my scientific goals, the more I was being pulled into an academic life that was not suited to truly honouring my soul. Although I loved my work and my topic, I was increasingly bound to my desk without ever stopping to engage my mind in scientific challenges, and a huge part of me felt distant from the very reason I embarked this career to begin with.

At the end of my Masters degree I met Craig Foster, filmmaker, naturalist and co-founder of the Sea Change Project for the first time, during a field outing to the sea shore. Something between us clicked. Craig’s nature immersion approach was what I had lost over time. Being together in the wild reunited the immersive part of my mind with the part that had been through years of scientific training and captivated my eye for detail. I saw what Craig didn’t, and Craig observed things I couldn’t see. It seemed like our skills collided in a togetherness of endless curiosity, joy and love for nature. And the ocean replied by inviting us deeper into her magical world.

After all it felt like I was further away from the ocean than I had ever been. I had to dig deep to find my will to move towards the coast. But the only times things seemed to lighten up was when I was in or near the sea. My chronic pain seemed to diminish in the vastness of the ocean. I would go as often as possible and gently grew the windows of a pain-free state of mind. Change did not occur over night, but I dedicated myself to strengthening my healing relationship with this environment. It took half a year to get a bit more independent. From January 2019, I went diving every day. My body adapted to the cold. Seemingly cold and scary, with sharks roaming at the edges of the kelp, the hidden world of the Seaforest became my second home.

As the year went on I was progressively feeling better. By winter I was in the water almost everyday either by myself or with my friends. Still struggling on land I was now a strong freediver and swimmer. Wonders kept opening up. A whole garden of soft coral sea pens living in the sand. See-through chokka squid paralarvae coming into the shallows from the deep. Every day there was something new to focus on, distracting me from physical pain.

As World Ocean’s Day 2019 approached, I was deep into my whole kelp forest and ocean-healing journey and felt particularly excited. World Ocean’s Day is also my birthday and this year it was like the beginning of a re-birth. I had been away for two weeks at a conference overseas and my knees felt vulnerable. I had spent my birthday eve and night at Craig’s with friends and in the morning as I walked to the window and gazed at the sunrise over False Bay, I just turned and said to my friend Faine, “I think today we are diving with a whale”. I did not know where that feeling came from.

Once in the water I started investigating one of the octopus dens near the kelp edge when Faine and Chryssea, another friend, suddenly called me over from a little bit further out. When I reached them and saw their faces I knew something had happened. Chryssea was near-shocked. I felt how their energies had changed. Then Faine showed me a picture of a Humpback whale she had just taken. The picture revealed how close it came. How did I dive 40 meters away from them and not see it? Normally these whales surface a lot, but this one didn’t. Or I missed it in my excitement? As happy I was for the two of them, I would have died to see the whale too.

I could feel an indescribable mixture of happiness for my friends, and a big ugly, jealousy-disappointed ego-clump sitting somewhere in my chest. It had been an absolute childhood dream for me to see a whale while diving. We swam a bit further along the kelp and into False Bay, but the whale had disappeared. Sadness crept up inside of me. I got very cold and told the girls I wanted to swim back. On the way to shore I decided to focus on nothing else but the joy my friends felt. I already pictured them jumping around on the shore, hugging each other in laughter. Suddenly that nasty ego feeling went away, as if it dropped to the ocean floor, diminishing in the endless sandy-bottom habitat and being soaked up by the gently moving kelp fronds.

Right in this moment something humongous and grey approached me from the green-blue darkness. The young male Humpback had reverted to cross paths with us once more. I was in only 5 meters deep water, swimming at the surface and it swam straight towards me. There was no time to do anything or get out of the way. Nor was I able to grab my camera. For a moment I thought he would hit me, but he was quite aware of me in the water. Smoothly he glided towards me, and then tilted his body to the side. I went under a bit and from two meters away I looked into a huge and gentle black eye. It was clear that this whale was a friend. In this moment, there was nothing else than understanding. Time stopped. The right flipper gently swept around me. I was tempted to grab it but a 2.5 meter long whale flipper can easily kill a human. I moved gently and slowly. Some kind of internal force started moving my arm. As I reached out slightly, my fingertips just touched his back. The whale turned sideways and looked at me once more, and then moved on. As I looked back I saw how he swam just underneath Faine and Chryssea in a similar fashion. I had tears in my eyes. The smile on my face pinched the rubber seal of my mask and let the cold seawater in. I looked at Faine and Chryssea. The three of us just laughed. We stayed in for a little longer and the whale swam back to us one more time. When we got out of the water, freezing cold, I could not believe how privileged I was. For the entire day my senses were heightened. My mood was incredible. We laughed and joked in pure happiness. It was one of the best birthdays, best World Oceans Days, best days of my life. I was home.

Just the next day we received a phone call. One of the octopus fishing traps had entangled and killed a whale just 3 kilometres down the shore. It was already getting dark but Chryssea and I went to see it. Established under an experimental fishing licence with no scientific data, and selling octopus mostly to overseas markets, the octopus fishery in False Bay had been controversial for some time.

The dead whale was floating next to a fishing buoy about 1.5km offshore, clearly visible but too far away to see anything specific. Was this potentially our whale we had met a day before? As we were standing at the shore observing seagulls flying over the cadaver in the distance, two other, larger Humpbacks appeared near the kelp edges, just 10–15 meters away from us. Their breathing sounds enriched the stillness of the fresh evening air. No other human was there. It was a grotesque scene. An extreme duality of beauty and sadness. I needed to sit down, my legs couldn’t hold my body. We watched the two whales for about an hour, the seagulls still circling the cadaver as it got darker. At some stage Chryssea whispered, “Jannes, they are talking to us”.

I am a scientist. It is my profession to find evidence, and it is hard for me to believe that these whales were trying to convey a message to us. They probably didn’t even notice two small primates sitting on the shore, but there was something about the integrity in which my friend said those words that created a feeling in me of “I think you are right”. And her words made me burst out into tears. I tried in my head to ask the two whales what they wanted to say. I did not get an answer, but there was no doubt about the strong message in this situation.

After a short night I found myself making coffee at 5 am in Craig’s kitchen. I had to know whether it was the whale I met in the water two days earlier. We knew that boats would soon be going out to the carcass, to cut it free and trawl it to the nearest slipway. I had to be on-site before them. We contemplated swimming out to the whale, but that would have just been mad. We discussed all the options and a good 1.5 hours later I was preparing a kayak. We were also concerned about the weather forecast.

Paddling along the beautiful coast of the Cape Peninsula, with a rising sun over False Bay, we could see the whale carcass from the far distance. The closer Craig and I got, the more bizarre it looked. Like a humongous floating device. Next to the dead creature floated the actual fishing buoys that marked the octopus traps. To our horror, just as we reached the scene there was another whale. A large Humpback, perhaps one from the night before, swam right into one of the ropes. It was a bizarre situation. Us alone in the kayak in this beautiful space, the dead whale, the wind howling, swell rolling and the sun rising in the distance behind the mountains. We heard the big blow of the whale that had just swam into the rope and luckily freed itself quickly. We were shocked at the dead whale whose tongue had swollen to a massive size, like a balloon that was about to burst. As we reached it, I immediately saw that it was not a Humpback but a rare Bryde’s whale, a fast and notoriously understudied animal. I had never seen one from this close.

The wind had started picking up a lot and we struggled to steer the kayak. I took a few seconds to acknowledge this moment, and to honour the dead Bryde`s whale. I was very emotional. Being out here, with my friend, fighting the elements. A feeling that is hard to forget. After a large wave had almost knocked us over we paddled back as hard as we could. With the last strength we made it to the shore.

The rest of the day went by like in autopilot. The Bryde’s whale carcass got towed into the slipway. I don’t remember everything but trying to somehow make sense of all of this I was taking a lot of pictures and was standing at the side watching a lot. The ropes of the octopus trap had pulled down the whale’s jaw. In its panic and death struggle it probably dislodged the jaw bones, and twisted the rope around its tail, cutting through the skin and slicing thick fat layers down to the bone through all the strong muscle tissue. As I walked alongside the 12-meter long animal, its skin felt smooth and soft drying out in the sun and wind. I observed the governmental department taking measurements and samples. A long knife went through the blubber like it was butter. Visible underneath was the fresh red meat with muscle fibres as thick as small earthworms; tissue samples for laboratory analysis. Meanwhile the whale’s blood had coloured the turquoise waters in the slipway into a dark reddish blue.

A day before it had been a young male in its prime. Hard to imagine that a creation perfectly adapted for water had actually drowned. Drowned because of our failure as humans. Now it was lying on a truck, secured with big straps over its body. Ready to be carried away to a landfill. It was a scene I only knew from pictures of whaling that took place in the centuries before ours. But this animal’s death here was the opposite of purpose. Nobody wanted it to die. Certainly I never wanted to witness this.

Over the next days there was an uproar about the whale’s death in the media. Most interesting was perhaps how this topic gained its very own unstoppable momentum. The whale was everywhere. Our telephones did not stop ringing, but mostly other organisations and private people started taking the topic on. I felt that the fishermen were blamed very harshly when in actual fact the situation was very complicated. One last relief was that our Humpback whale was still swimming out there. I thought about him a lot.

Less than two weeks later we got notified that another whale got trapped in the octopus fishing ropes and had drowned. I had merely recovered from the first disaster. The next morning I again found myself standing at the pier of the same slipway, waiting for the boats to tow the new carcass in. The hand holding my camera inside my pocket shivered. Emotions off. Autopilot on. As the animal was pulled into the shallow waters I saw that it was a beautiful male young Humpback. The exact same size as the whale we swam with two weeks earlier. I was terrified. While the governmental department took their measurements again, I was shivering and investigating this whale in a very different way, looking for individual identification cues. Humpbacks have unique skin patterns. I would have to compare earlier pictures to see if the drowned whale was our big grey friend.

The deaths of the whales, as horrible as they were, also brought magical creatures to me, which even I as a crustacean biologist, had never seen alive. Whale barnacles, creating the unique skin pattern of Humpback whales, grow on and in the skin in many areas. And to these large barnacles, strange-looking Rabbit-ear barnacles attach. These skin parasites were still alive when the whale got towed into the slipway. In all my horror I was also enthralled. Furthermore, many areas like the furrows on the whale’s lower jaw were covered in carpets of Whale lice amphipods. Amphipods are small shrimp-like crustaceans, these ones with impressive claws to hold onto the whale. They eat both algae growing on the skin but also flakes of the whale skin itself. These communities travel thousands of kilometres on whales. I took hours to look at them, photograph them, and collected a few organisms that fell off as the whale got pulled onto the truck. Loosing their host they would have died anyways as they need the whale to survive. In some ways it was a great privilege to be drawn into their secret lives even if the circumstances were difficult to deal with.

Not that it would change anything to the whale that died, but I was somewhat relieved to confirm later in the day that this Humpback was not our whale. It gave me some piece of mind that he is still swimming out there. A couple of days after, after another slew of media reports, letters and opinions sent to government, a temporary moratorium was called on octopus traps. Later, the minister implemented rules under which the gear had to be adapted so that ropes will not entangle whales anymore. With the traps out of the water the situation calmed down.

Now, a year later the rumours are that new gear is in place, showing that solutions to less destructive fishing can generally be found if discussion around a challenge takes place. South Africa is generally good at this, which gives hope for bigger challenges. The octopus fishery killing whales was a challenge that happened in front of our eyes, in the same waters in which we dive every day. Catching octopuses in South Africa is still highly controversial. And there are much more destructive fisheries in our national waters too.

Covid-19 has undoubtedly brought a lot of new challenges and different viewpoints into our world. And today, job and food security might be seen in a different light. Catching fish for export is a model that has proven maladapted to serve local people very well. In my opinion, the prices that octopuses, rock lobsters and sharks gain on foreign markets don’t cover the environmental cost of losing these animals to our precious ecosystems. And who of the overseas buyers of fish pays extra for the sad ‘by-catches’, like the deaths of whales? Is it not time to realise that globally traded marine resources generally diminish the intrinsic value of South Africa’s big ocean treasure, and give comparatively little back in return?

Today, as we celebrate World Oceans Day 2020, it is exactly one year since Chryssea, Faine and I swam with the whale and a lot has happened in the world and to me. There are several things that I have learned for myself. A debilitating disease can only be treated when nurturing a healthy mind. The constant focus on my pain had actually made the problem worse. And after the whales and countless other powerful experiences in the Seaforest I have more space in my mind and soul for bigger things.

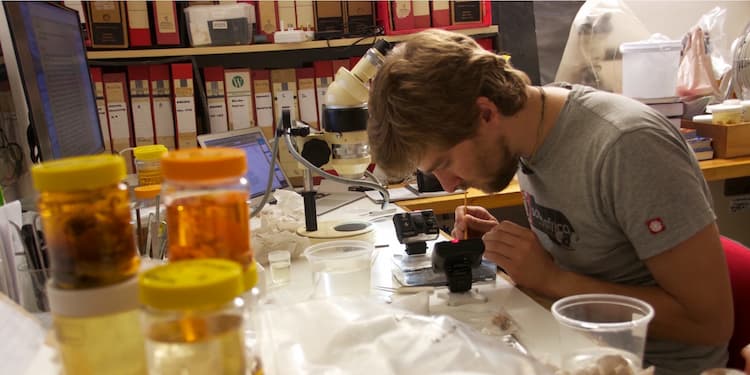

During lockdown I worked through the scientific samples that had accumulated in my freezer. This included some of the specialised barnacles and Whale lice from the dead Humpback. I preserved and dried a few of them on a tiny piece of whale skin from the same whale, and casted them into a resin. This little piece of art also got fitted with a small light. With a special whale-background I carved it into ocean driftwood, and it is now built into my bathroom wall next to the mirror. It is the first thing I see in the morning, and the last thing I see before going to bed at night. The Whale lice remind me of the whales, all the extraordinary experiences in the forest, and every day they motivate me to continue with my marine biology and the Sea Change Project to reveal to the world how remarkable and important the Great African Seaforest is.

As I am finishing the editing of these last lines, a Humpback whale is flapping his large flipper a few hundred meters away from me in the still winter evening waters of False Bay. Perhaps it is our friend and he made it back from Antarctica. It is World Oceans Day. I smile.