Two Creatures Turning Our Thinking Upside-Down

Jannes Landschoff & Craig Foster

Dr Jannes Landschoff

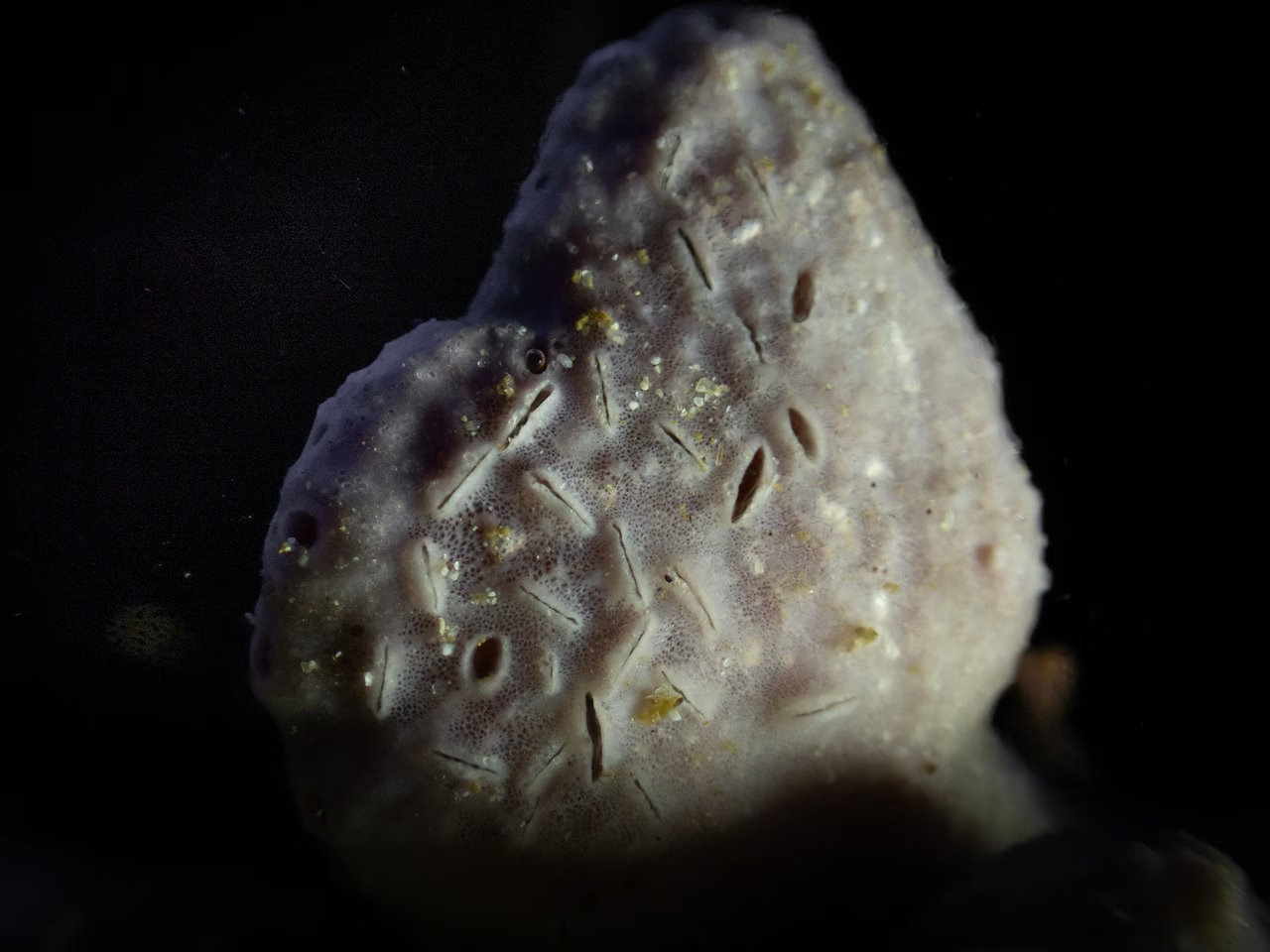

One late afternoon, torch in hand, a friend and I pottered around in the shallows looking for tiny critters. I saw a strange pattern on a blueish sponge: small slits on the surface, with animal feelers sticking out of them. An Upside-down amphipod (Policheria atolli)!

What was unusual about this sighting was that colonies of these delicate, 5mm-long creatures are usually seen on the body walls of ascidians, which are sessile organisms that grow on rocks. However, these ones were living on the sponge, each amphipod lying upside-down in an excavation on the surface. To protect themselves from predators, these little creatures have nippers on the end of their legs, which can be used to pull their burrows closed – a bit like drawing a curtain. Other specialised legs pump water through the burrow and capture food.

I’m not sure if this is harmful to the sponge, or if the amphipods may even be beneficial in some way, such as defending the surface from other intruders or sponge-eating animals. What I do know is that the accumulation of little animals such as the Upside-down amphipod keeps an ecosystem healthy and functioning.

Biodiversity is so important. After learning that these organisms also live in sponges, I can’t help but wonder if they are the same species as the ones living on the ascidians. Our foundational, taxonomic scientific knowledge of species in South African marine systems is still limited, so it’s always possible that there are many more than just one species.

Upside-down amphipod (Policheria atolli). Photos: Jannes Landschoff

Craig Foster

During one of my daily dives, I spied a camouflaged juvenile Cape sole lying on the sand. I glided down as gently as I could to take a picture. As I moved closer to take another one, something extraordinary happened. The sole vaulted off the seafloor in a lightning-fast lunge using its muscular body for propulsion. It landed upside-down on the back of my hand, and remained dead-still – even when I surfaced and took another quick picture.

My mind scrolled through its library of thousands of underwater images and landed on one: a bluefinned gurnard, a fish that looks like an underwater dragonfly. On the gurnard’s back was an upside-down juvenile Cape sole. This behaviour had always mystified me, but now I had an idea about why it happened.

Gurnards hide in the sand with extreme camouflage. Half-buried, they use their modified ray fins to slowly probe the sand for prey. Then they unfold their ‘wings’ in one of the most remarkable natural history displays. These bright pectoral fins startle predators, but also act as mock shelter for prey animals in the sand.

The gurnard in the picture I had taken six years before had invariably been probing the sand as it hunted for prey – and the Cape sole was on its menu. The fin rays had probably touched the sole and the gurnard had attacked with its large mouth. However, the sole had been too quick – and too smart. Instead of fleeing along the sand where it would tire quickly and be eaten, the sole had vaulted onto the gurnard’s back and stuck there upside-down. While the gurnard had flared its magnificent fins to try to shrug off the sole, the hitchhiker had clung fast.

Finally, I’d figured out the mystery, and in so doing had created another two mysteries. Why had the sole landed upside-down on the fish and on my hand? And how does the sole escape off the gurnard’s back without being eaten?

Perhaps the sole has a smooth and slippery underside to move across the sand with little friction, so sitting right-side-up would result in the fish sliding off the predator’s back, so it adheres with the rougher topside.

The ocean is filled with so many of these mysteries. And this is what calls me back again and again and again. Learn more about our 1001 Seaforest Species project here.

Cape sole evading attack. Photos: Craig Foster

1001 Seaforest Species is a collaboration with, and made possible by, Save Our Seas Foundation