Celebrate South Africa’s Marine Protected Areas With Us

Pippa Ehrlich & Swati Thiyagarajan

One of the most exhilarating things about exploring the ocean is the wonder of the unexpected. The Great African Seaforest is home to thousands of species, some that have not yet even been scientifically named (our 1001 Species Project aims to help with this) and every time you set foot in the kelp forest you are opening yourself up for an experience that you cannot predict. You might find yourself eye to eye with a curious otter or seal or surrounded by a silvery shiver of spotted gully sharks, or witnessing an octopus in the midst of some ingenious act that you never imagined possible. These encounters can be deeply life affirming, but are impossible to plan.

Then there are those special pockets of the kelp forest that offer a different kind of experience: an opportunity to travel back in time to glimpse what the kelp forest might have been like when our seas were more abundant and home to not just many more fish, but to a far greater diversity of species. These time capsules make up South Africa’s network of marine protected areas and they have become biological savings accounts for our marine heritage: a vast coastline exceptionally rich in endemism and biodiversity.

Here are some of our favourite MPA residents:

1. Red Steenbras (Petrus rupestris)

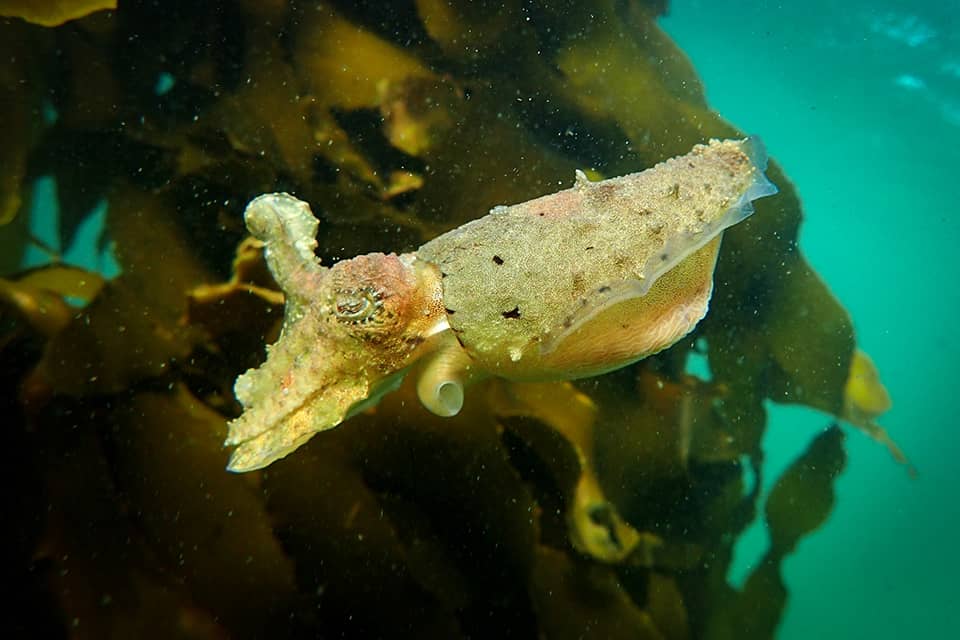

2. Tuberculate cuttlefish (Sepia tuberculata)

3. Pore-bellied cuttlefish (Sepia typica)

4. Kynsna seahorse (Hippocampus capensis)

5. Brown shyshark (Haploblepharus fuscus)

6. Cape knifejaw (Oplegnathus conway)

7. Black musselcracker (Cymatoceps nasutus)

8. Abalone or perlemoen (Haliotis midae)

9. African penguin (Spheniscus demersus)

10. Humans (Homo sapiens)