Chewing Gum and Bird Spas:

A Tracking Tale of Two Cities

By Helen Walne & Craig Foster

When Craig travels to London and New York, he feels out of place – until he discovers that a wild mind can still thrive in a tame world.

I’m on a multi-city tour in America, and I’m feeling far from home. Steel and windows flash past and there is concrete everywhere. Cities are foreign places to me, with their bristling forests of tall buildings. I’m used to a softer jungle filled with fish and fronds. But I’m also grateful to be here as part of a promotional tour for my book, Amphibious Soul, which explores how humans live divided lives, with one foot in the ‘tame’ world and the other in the ‘wild’ world.

In San Francisco, our cab driver, Julius, has a soothing baritone voice that would put James Earl Jones to shame. Driving me home from an interview with Professor Dacher Keltner, who has done research into the role of nature in creating a sense of awe, we talk about how people have been severed from nature and how vital it is to mend those threads.

Suddenly, a black raven swoops down, almost touching the car. An hour earlier, a driverless car – unsettling, dystopian and strangely macabre – had cut in front of us. If ever there was a place where the wild and the extreme tame meet, this is it.

I’ve been tracking animals underwater and on the coast at the tip of Africa every day for 12 years. It’s akin to being a nature detective – piecing together trails, tracks and marks to better understand animal behaviour. Now I have to break that routine for the first time and travel for a month to the US and the UK. My book is about finding the wild in a tame world, so I set myself a challenge: can I use the tracking techniques I have honed in Africa in New York and London?

Craig Foster tracking in the Great African Seaforest- Photo by Scott Ramsay

I begin in New York, searching for signs and patterns, but nothing looks familiar. I know the Great African Seaforest so well. I read it like -braille. But here, my tracking fingers seem numb and I’m struggling to feel my way around. But I’m determined to take on the challenge. So the next day, I team up with my friend, editor, writer and tracking enthusiast Sarah Rainone, to test if urban tracking is possible. We worked closely together on my book for two years but have never met in person, so it’s exciting to put into practice what we put down on paper.

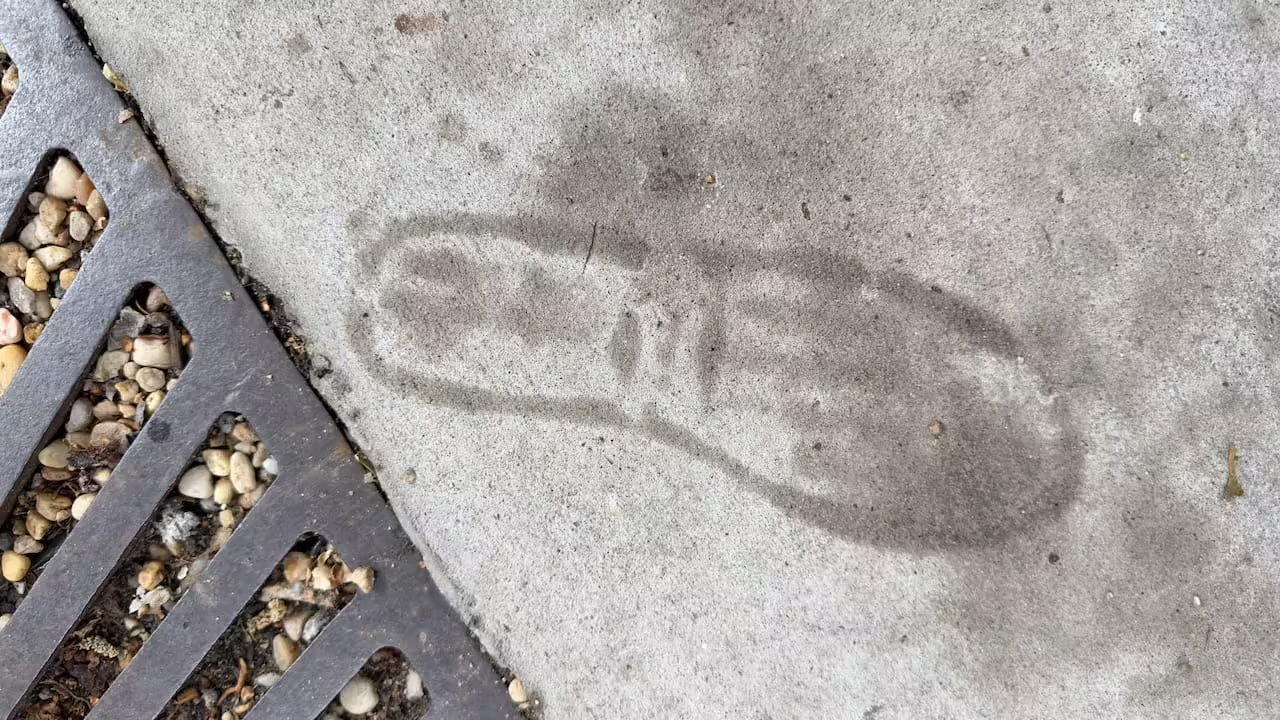

Today, good fortune is on our side as the overnight rain has left the city full of puddles, and clear tracks of people and animals can be seen criss-crossing the cold concrete. We follow their trails, trying to determine the size of each person, their speed, the way they place their feet – even their wealth, based on the wear of their tread. Most people have moved fast in a focused way. Many sizes of dogs have walked with their owners, keeping to the curbs where the more interesting smells collect.

Tracks in New York City - Craig Foster

Xam San engraving of human track, Northern Cape - Craig Foster

Tracks in New York City (left); Xam San engraving of human track, Northern Cape (right) - Craig Foster

We see where a person repeatedly wiped his large foot on a small patch of gravel trying to remove something unwanted – maybe dog poop. Then I notice a strange track that looks like two bicycles riding side by side and then going further and closer, like a pair of synchronised snakes. After a few minutes, we work out it is a baby stroller with front wheels narrower than the back, with the result that the tracks merge closer when it turns a corner. Sarah spots three rats running on a track in the nearby undergrowth and I hear a small bird alarm-calling, warning other birds of the rodents’ presence. Sarah has never been a fan of rats, and once sought refuge at a neighbour’s after coming across a huge one in her Manhattan apartment. But now she looks at them with curiosity and even empathy. ‘They’re so smart and resourceful,’ she says.

Stroller tracks - Craig Foster

Cape sand snake - Craig Foster

Stroller tracks (left); Cape Sand Snake (right) - Craig Foster

We see small holes in the hard dirt, like little bowls, in which birds are having dust baths. The grit particles get into the joints of tiny parasites and act like a natural cleaning system.

Even discarded chewing gum has a tale to tell. It’s often dropped where people stand before entering a building, which indicates that the edifice is viewed as having more status than the street. This hierarchy is also seen according to where the gum is cleaned away: main thoroughfares are often scrubbed of the sticky clumps, while side streets are left pockmarked with gum. Looking closely, Sarah and I also spot imprints and impressions in discarded gum, perhaps the result of wheels trundling along the pavement. While they’re not intentional or as artful, they remind me of the work of London artist Ben Wilson, also known as ‘Chewing Gum Man’, who decorates street gum with miniature artworks.

Photo of gum art by Ben Wilson

Photo of gum art by Ben Wilson

Photos of gum art by Ben Wilson

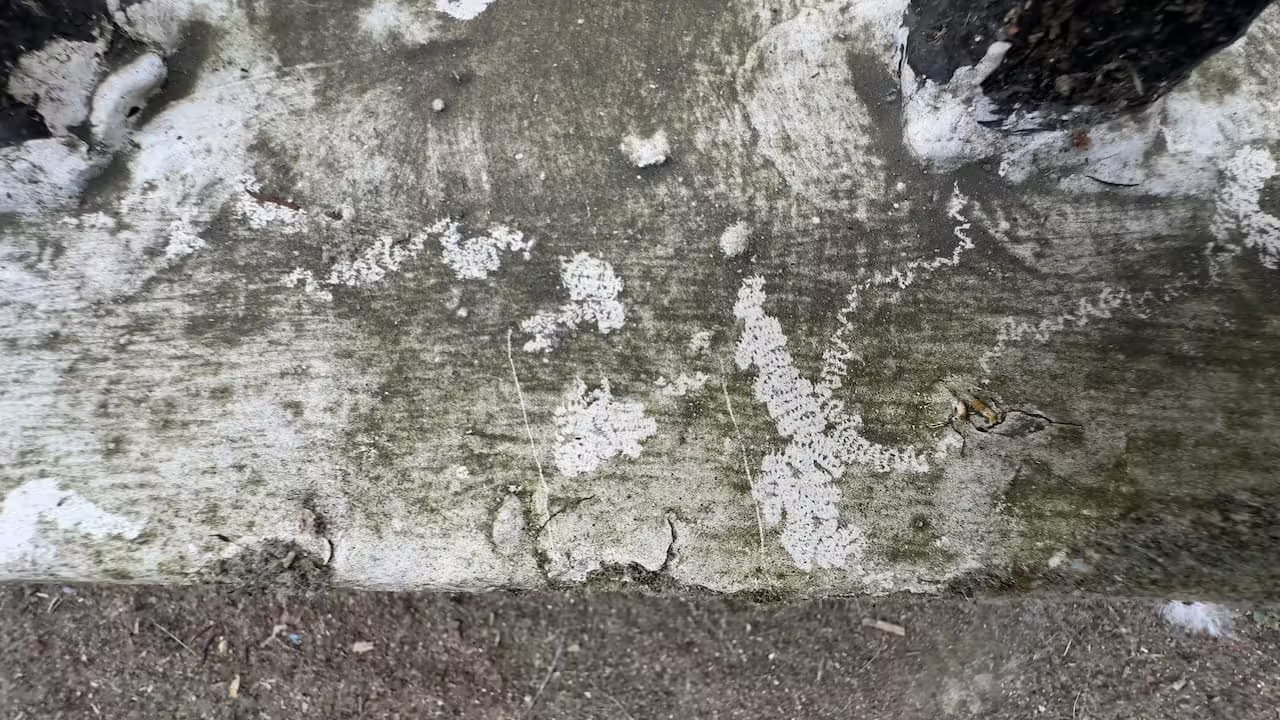

Radular marks on the pavement - Craig Foster

Limpet feeding marks on kelp - Craig Foster

Radular marks on the pavement (left); Limpet feeding marks on kelp (right) - Craig Foster

There are plane trees that show evidence of squirrel gnawing, but Jackie figures out they are also shedding their bark perhaps to fight off pollution and toxins. When I see trees in the city, I can’t help wondering what’s going on underground and, as scientist Suzanne Simard posits, whether they are able to communicate via fungi, as they do in the wild.

Plane trees shedding bark - Craig Foster

Detailed view of missing bark - Craig Foster

Plane trees shedding bark (left); Detailed view of missing bark (right) - Craig Foster

We circle around tracks embedded in dried concrete: the paw prints of a massive dog are revealed when we push aside dead leaves after initially spotting a sliver of track. There are prints of cats, humans and birds – all embossed on the city’s surface forever. We gape up at a magnificent 1000-year-old cathedral clad in knapped flint, a substance believed to have originated from the ocean when spicules of sponges silicified in cavities created by molluscs or crustaceans. Another circle: sea and, now, city.

Knapped flint cladding on the Southwark Cathedral - Craig Foster

Taking a break under the shade of a tree, Jackie reflects on the experience, laughing. ‘I’d been looking forward to this day, but I assumed we’d be heading to a park, a riverside, or some wetland.’

She says after seeing the radula marks, she was transported. ‘It’s like the noise and crowds seemed to evaporate. I was in a parallel universe – curious, engaged, elsewhere. These traces of creatures were guiding us, each with different profiles. And then I wondered how a radula actually works.

A Marine snail feeding with its toothed tongue called a radula - Craig Foster

In the city, it’s all too easy to get swept up in the urban flow – the mad, mindless dash from one engagement to the next. I found myself immersed in a wild place far away from any remote mountain top, deep cave or jungle, experiencing stillness, awe and wonder on grubby curbstones. Who knew?’

Next I team up with my friend, animal communicator and expert tracker Anna Breytenbach. This challenge is getting increasingly interesting and I’m discovering that city tracking is not only possible, but fascinating and enriching.

The first thing we notice are ancient-looking symbols engraved into the curbstones. We spot two crosses and a triangle, reminiscent of the engravings of the San people, with whom I worked for many years as a filmmaker and who taught me how to track. It’s a wonderful circle: me using skills learnt from the oldest surviving culture of Southern Africa to map out redolent markings in one of the world’s most contemporary cities. These symbols are Victorian parish boundary markers that demarcated ‘municipalities’ in the city.

Cross engraving in London - Craig Foster

Ancient symbols on London streets - Craig Foster

Cross engraving in London (top left); Ancient symbols on London streets (top right) - Craig Foster

Further along, we sit and watch a squirrel scavenging from a bin. She seems to have a skin problem – probably mange – and her teats are visible as she reaches up to feed on leaves twirling in the breeze. She obviously has young nearby and is searching for as much nutrition as she can. A pigeon with string tangled around its foot hobbles past, leaving curious tracks on the damp pavement. As expected in a city, the marks of human activity are everywhere: the spatters of an oily substrate resembling a pavement Jackson Pollock; building corners that have been repeatedly rubbed, possibly as pedestrians brush up against or grab hold of the wall as they peel off; the tracks and trails of scores of footprints representing varying strides, speeds and status.

An urban squirrel foraging - Craig Foster

Pigeon with damaged foot - Craig Foster

An urban squirrel foraging (left); pigeon with damaged foot (right) - Craig Foster

‘This is so much fun,’ says Anna. ‘We’re imitating the strides and body movements to replicate the human tracks and signs we found. It’s like some sort of embodied empathy. By letting our own bodies re-enact what happened opens up surprising insights into the experience of the ones who passed through a place. We directly feel their choices: what made them stop or start, where their visual focus was, even their state of mind.’

She also points out that unlike animals, who are at one with their environment and focus on conserving energy, city humans expend a lot of energy in their detached and distracted state. ‘If an animal comes across a puddle, they just go through it,’ Anna says. ‘But with all the trappings of urban living, like clothes and shoes, humans step around a puddle to avoid it.’

I end the day doing an intertidal walk on the Thames with master swimmer Bridget Trefgarne. Pining for water, I’d hoped we could swim in the river but we were warned against it due to its toxic levels of e. coli and other pollutants. We settle for an exploration of the banks and shallows to see if there is anything alive. It’s better than I thought. We find flatworms, amphipods, feeding ducks, flint and old pottery. There are also predated crabs regrowing their legs, just as they do back home. Scouring river banks for artefacts is becoming a popular pastime in Britain. Called ‘mudlarking’, it is a practice that harks back to Victorian times, when destitute people hunted for things they could sell. Nowadays, it’s an archaeological quest for fragments of centuries-old history; a form of tracking.

Thames crab regrowing its legs - Craig Foster

Great African Seaforest crab regrowing its legs - Craig Foster

Thames crab (left) and Great African Seaforest crab (right) regrowing their legs - Craig Foster

At the end of our scouring mission, Bridget surveys the river. ‘My mind feels calmed, just from looking down and filtering out all the visual distraction of the city. By focusing on a defined area around me, it’s like I become a master detective of my own universe.’

As the Thames’s formidable tide rises, threatening to strand me and Bridget on a tiny island, I gaze at this vast city. Around me is water rushing in from the North Sea. On the streets above us are engravings, tracks, secret animal lives and patterns that form worlds upon worlds and give up a cosmos of knowledge. And, suddenly, I’m connected to everything, just as I am back home in the kelp. As I step off the island and wade through the shallows, I look back. The incoming water has washed away my closest tracks, but there on the muddy outcrop, the tread of my boots is still visible. Here I am. And there I am.