Can an octopus do geometry?

Jannes Landschoff

In our quest to build relationships with 1001 Great African Seaforest Species, it is most obvious that we began the count with #0001 – the Common octopus. At the beginning of this year we published an original research paper in the science journal “Marine Biology”. Our research findings show how precise octopuses are in their ability to drill into the shells of their prey.

In False Bay, South Africa, the Common octopus preys on a plethora of marine invertebrates, mostly snails and bivalves which have hard external shells. So while it is easy for a hungry octopus to catch these slow and probably delicious snails, the challenge is on when an octopus needs to get to the juicy meat inside. Either the snails stick firmly to a rock or they retract into their shell houses, unreachable for the octopus. The octopuses solution to getting its prey is a little drill inside the mouth. Octopuses spend hours making a tiny hole in the strong, calcified shells of their prey through which they inject a venom from their salivary glands. As a result the snail drops all defences and can be easily pulled off the substrate it sits on. The meat can then be extracted for consumption.

Having observed this many times in the wild the octopuses slowly taught us how they do this. Inspired by their workings we started looking at thousands of shells that octopuses had drilled. What beach goers may be unaware of is that many shells they see lying around have tiny, teardrop-shaped holes, indicative of an octopus predation! Looking at these various shells again and again, we started to see patterns. We saw that shells of the same snail species had holes in the same places. So this made us wonder where do octopuses drill into the shell and why? There are many different possibilities!

This mystery was tackled through research we did with UCT marine biology student Gareth Fee. We were also supported by “Professor Octopus” Jennifer Mather from University of Lethbridge, who had already helped us while making My Octopus Teacher.

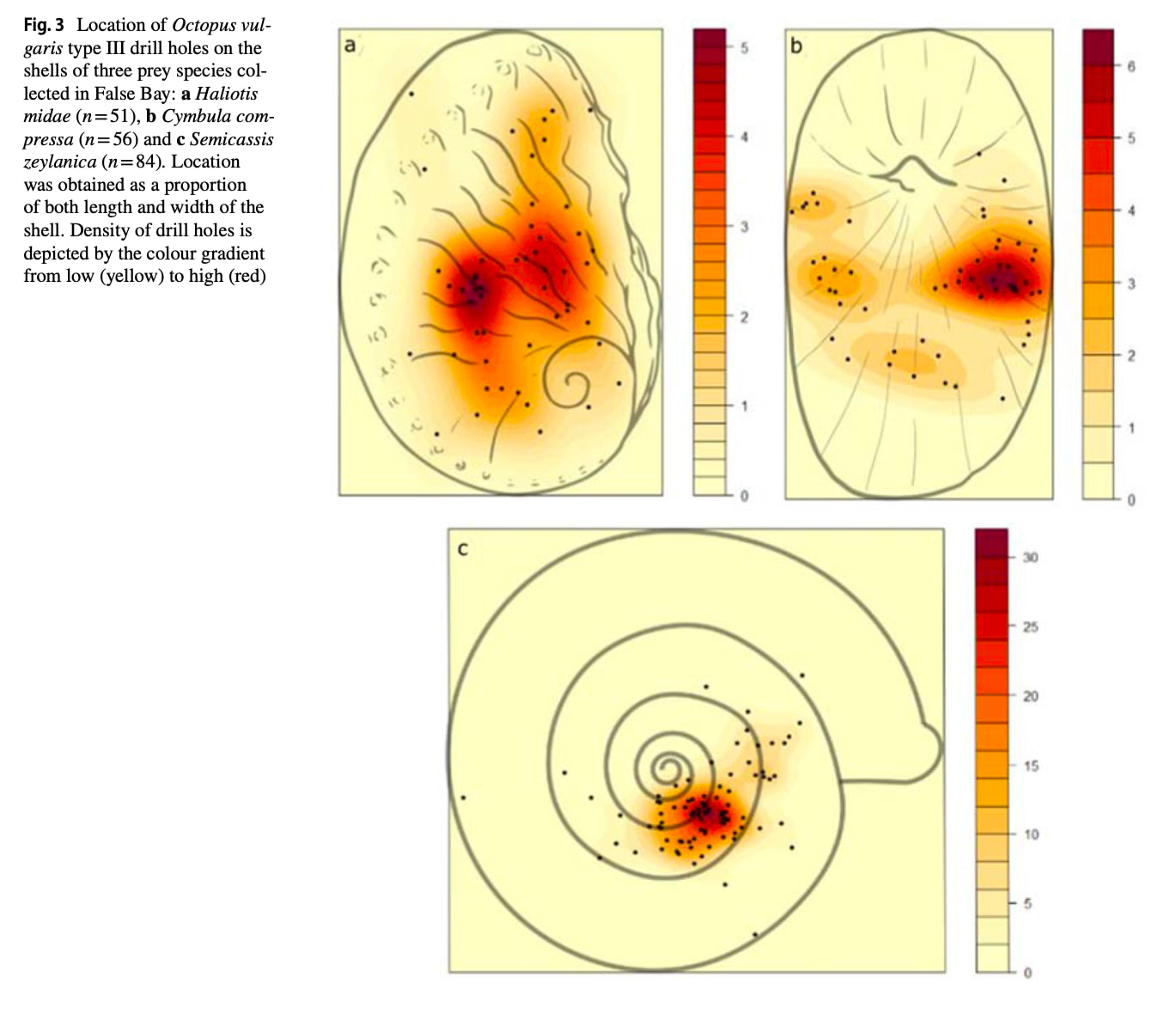

For Gareth’s research we collected sufficient numbers and varieties of shells from many different octopus dens. We then tested the hypothesis that octopuses would not just drill anywhere at random, but that they would be strategic in choosing a drilling location. Moreover, Gareth looked at three different species of prey – the Abalone, the Kelp limpet, and the Helmet snail. The idea was that in order to “hit” the underlying target tissue with sufficient venom (e.g. the muscle they use to cling on tightly to a rock) octopuses would have to drill different prey species of differently-sized and shaped muscles at different levels of precision. First, in the Abalone the large muscle under the shell would be a big target, hence an octopus would not need to choose the drilling location very precisely. Secondly, this area would be relatively smaller in a Kelp limpet that has a smaller attachment muscle. Thirdly, we saw an even smaller target area in the Helmet snail. If this was true then this would also mean that octopuses would somehow need to “measure” where to drill – they would have to do some kind of basic maths and geometry!

Analysing all these shells Gareth plotted the drill locations onto two-dimensional heat maps, and we could show that octopuses indeed measure and choose their drilling locations carefully. Especially the precision at which octopuses drilled into the Helmet snail astounded us. Of the 78 shells analysed, the absolute majority was drilled in a very constricted region. What we can infer from these data is that octopuses must use the spire, the lip and aperture of the shell as a landmark from which they measure.

I often think of octopuses as the eight-armed people of the kelp forest. This concept is easy to follow when one realises how clever they are, how clever they have to be in order to survive. The idea that they do geometry and maths (in the way we do) may be a little far-fetched for some of us. But choosing the drilling location correctly is essential for an octopus. If it was not then the octopus people would not be able to get the food they need. And since this is not a species nurtured by parents once they hatch, each octopus has to teach her/himself how to predate on these various species. It most certainly takes great intelligence to do this effectively. With the octopuses teaching us how they operate, we realize that they are not so different to us!

footnotes

1001 Seaforest Species supported by the Save Our Seas Foundation

Photos by Jannes Landschoff and Craig Foster