1001 Seaforest Species

The 1001 Seaforest Species project brings ashore the stories of 1001 organisms that call the Great African Seaforest home. A scientific inquiry with the art of underwater tracking and storytelling at its heart, core members Dr Jannes Landschoff, Emeritus Professor Charles Griffiths and Craig Foster unveil the secret lives of these creatures. This bid to build a lasting seedbank of species knowledge is driven by an urgent call to inspire awareness of and awe for nature.

Biodiversity – that breathtaking array of life on earth – underpins our survival, and knowing it is crucial for supporting its protection. The number 1001 draws inspiration from the tale One Thousand and One Nights, where a young woman’s endless storytelling keeps her alive night after night, eventually softening the heart of a vengeful king. Similarly, 1001 Seaforest Species seeks to keep Mother Nature alive by sharing her stories, species by species, fostering a profound sense of wonder and an urgency to protect her.

This evolving project is presented simply, with each species arranged numerically starting from #0001: the octopus, the animal that captured the world’s imagination in our Oscar-winning film My Octopus Teacher, to #1001: Homo sapiens, the human in the seaforest. Each animal has a story, and we are all connected in the miraculously complex web of life that is biodiversity.

Octopus

The octopus is our great teacher as she holds a special place in the ecology of the seaforest. We have perhaps got closer, and learnt more from her, than from any other seaforest animal. Nearly every kelp forest species is somehow linked to her behavioural complexity. Octopuses have shown us how they hunt up to 100 different species of prey, how they in turn avoid predation by seals and sharks, and how they master an unimaginable life of camouflage. For us she is the inspiration at the centre of the biological wonder that is Mother Nature.

Background

The oceans around the southern tip of Africa are diverse and unique. The warm, fast-flowing Agulhas Current carries subtropical waters from the Indian Ocean along South Africa’s east coast, contrasting with the cold, nutrient-rich waters of the Benguela Current on the west coast, where giant kelp forests thrive. This contrasting oceanographic diversity makes South Africa’s coastline globally important, with 33% of the >13,000 marine species known thus far being endemic.

Cape Point near False Bay marks a biological break point for marine species distributions and is home to the Great African Seaforest, a unique and diverse kelp forest ecosystem. Our team has explored and cherished this region for over a decade, helping it gain recognition as a valuable marine ecosystem. We carefully embedded the name ‘Great African Seaforest’ in all our media work, and in 2021 it was named a New World Wonder. This iconic status will help towards its long-term protection.

Aims

As environmental challenges threaten the last remaining wilderness areas of our planet, we use underwater tracking, marine biology research, and storytelling to:

- Foster a holistic understanding of the marine environment

- Connect people to nature, inspiring an emotional bond and care for the natural world

- Raise awareness locally and globally about biodiversity’s essential role in human survival, promoting active participation in protecting the web of life

- Highlight the significance of the Great African Seaforest to safeguard its iconic status and support its preservation

- Bridge gaps between the science-to-policy interface to inspire political action

- Encourage world business leaders to adopt a nature-centred value system

OUR THREE-PRONGED APPROACH

Underwater Tracking

An observational skill honed through presence and connection with the environment, tracking enables a deeper understanding of the seaforest, sometimes even the discovery of new species or novel animal behaviours.

Research

Storytelling

Beacon of Biodiversity

The Great African Seaforest and the ocean at our doorstep represent not just hope, but a living system that enriches our planet at a time when global awareness, policy and enforcement are urgently needed to restore the health of our natural world.

Our 1001 Seaforest Species project is centred around this remarkable kelp forest and the vital marine biodiversity it supports. Through documenting and highlighting the unique characteristics of the species within the Great African Seaforest ecosystem, we emphasise their interdependence and their crucial role in the health of the world’s oceans.

Our strategic objective is to accelerate global awareness of kelp forests in key domains, including the general public, the scientific and conservation communities, governments, multilateral institutions and businesses. We aim to inspire people worldwide to create conditions where such ecosystems can flourish and to energise individuals to take personal action in protecting biodiversity, leading to a deeper sense of purpose and meaning in their lives.

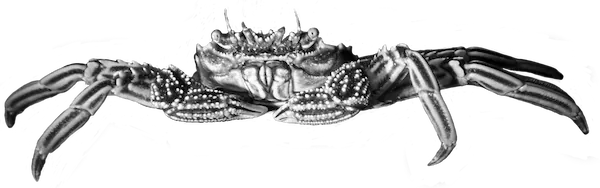

Rock Crab

Rock crabs are key players in the subtidal ecology of South African kelp forest shores, forming healthy populations of omnivorous foragers. While they hunt for small invertebrates, they must stay alert, as they are amongst the favourite food of the octopus. Rock crabs have an impressive escape mechanism: their flattened legs are perfectly adapted for quick swimming when needed.

App

We’re excited to launch the 1001 Seaforest Species app in 2025—a free, custom-built guide to the incredible marine life found in the Great African Seaforest. Designed with an intuitive species identification tool, the app will help users explore a range of categories, from fish to crustaceans and mollusks, and identify individual species with ease. This resource is tailored for the local marine community and anyone fascinated by ocean biodiversity. Highlighting rare and unique species found only in our region, the app will also contribute valuable knowledge to global biodiversity by including new discoveries and first-ever live images of marine life.

Social

#0047 Sucker-foot sea hare – Aplysia juliana

A rabbit in the ocean that whips up clumps of spaghetti? Well, not really. These large sea hares – some as big as rugby balls – are a type of sea slug and are so named because their rhinophores resemble bunny ears. These sensory organs allow the sea hare to taste, smell and detect chemicals in the water to find food and locate mates. And the ‘spaghetti’? These are the animal’s eggs, which they lay in cream-coloured tangles on various seaweeds.

This particular species is variably coloured, its whitish, yellow or dark-brown body spotted or striped in brown or black. The yellow and brown ones are almost delicious looking, as though made from custard and chocolate.

However, predators of these algae-munching animals are in for a surprise: Sucker-foot sea hares secrete a purple dye when disturbed – a behaviour known as ‘phagomimicry’. The dye consists of a melange of chemicals that mimic the smell of food, which overwhelm the predatory senses and make the sea hare undetectable. A true case of pulling a rabbit out of a hat!

#1001seaforestspecies #1001speciesproject #1001species @saveourseasfoundation #greatafricanseaforest

#0046 Giant jelly – Rhizostoma luteum

What this large jelly lacks in tentacles, it more than compensates for with mouths. Giant jellies, which are often washed ashore, lack a central primary mouth; instead, their four pairs of thick oral-arms are lined with numerous small mouthlets. The bell, firm and scalloped at the edges, can span up to 60cm, while the oral-arms may trail club-shaped appendages that stretch to twice that length. Though they drift gracefully through the water feeding on zooplankton, they too become prey when stranded on beaches, where plough shells eagerly munch on them.

@saveourseasfoundation #1001seaforestspecies #1001species #1001speciesproject #saveourseasfoundation

#0044 Elegant feather star – Tropiometra carinata

As the name suggests, this striking species has 10 straight, upward directed arms that bear up to 100 evenly spaced lateral branches (pinnules) that resemble the flight-feather of a bird. And seeing these animals in ‘flight’ is truly special. While they are usually attached to shallow reefs, sometimes among other smaller feather stars, they are capable of swimming when disturbed, their arms moving up and down in a slow, graceful movement, almost puppet-like. Elegant feather stars also use these arms to snag floating plankton or other organic matter, feeding the food via tube feet that line the pinnules into a groove running along the length of the arm. There, cilia (tiny, hair-like structures) propel mucous and food particles to the mouth, situated on the upper surface of the central disc. The pinnules have another important function – reproduction. While we’re still researching the exact process of this species, male feather stars store gonads in these branches, which rupture when the gametes are mature, releasing sperm and eggs into the water column. Here, they develop as planktonic larvae that then settle on the reef … and so begins a new generation of these yellow-hued wonders.

@saveourseasfoundation #1001seaforestspecies #1001species #marinebiology #seachangeproject

#0043 Stout seafan pycnogonid – Boehmia chelata

They might look like incy-wincy spiders but these animals are their own group – pycnogonids. What distinguishes them is a pair of ovigerous legs, specialised appendages behind the mouth parts used primarily by males for carrying eggs and for grooming. This small endemic species (only about 15mm in total) has an unusually stout body and legs and is bright pink or orange, allowing it to blend in with the branching seafans it calls home, and upon which it is thought to feed. There is still much to be learnt about Stout seafan pycnogonids, but what we do know is that the female releases eggs that are fertilised by the male, who then carries these on his specialised legs until they hatch – an example of true co-parenting.

@saveourseasfoundation #1001species #1001speciesproject #seachangeproject #biodiversity

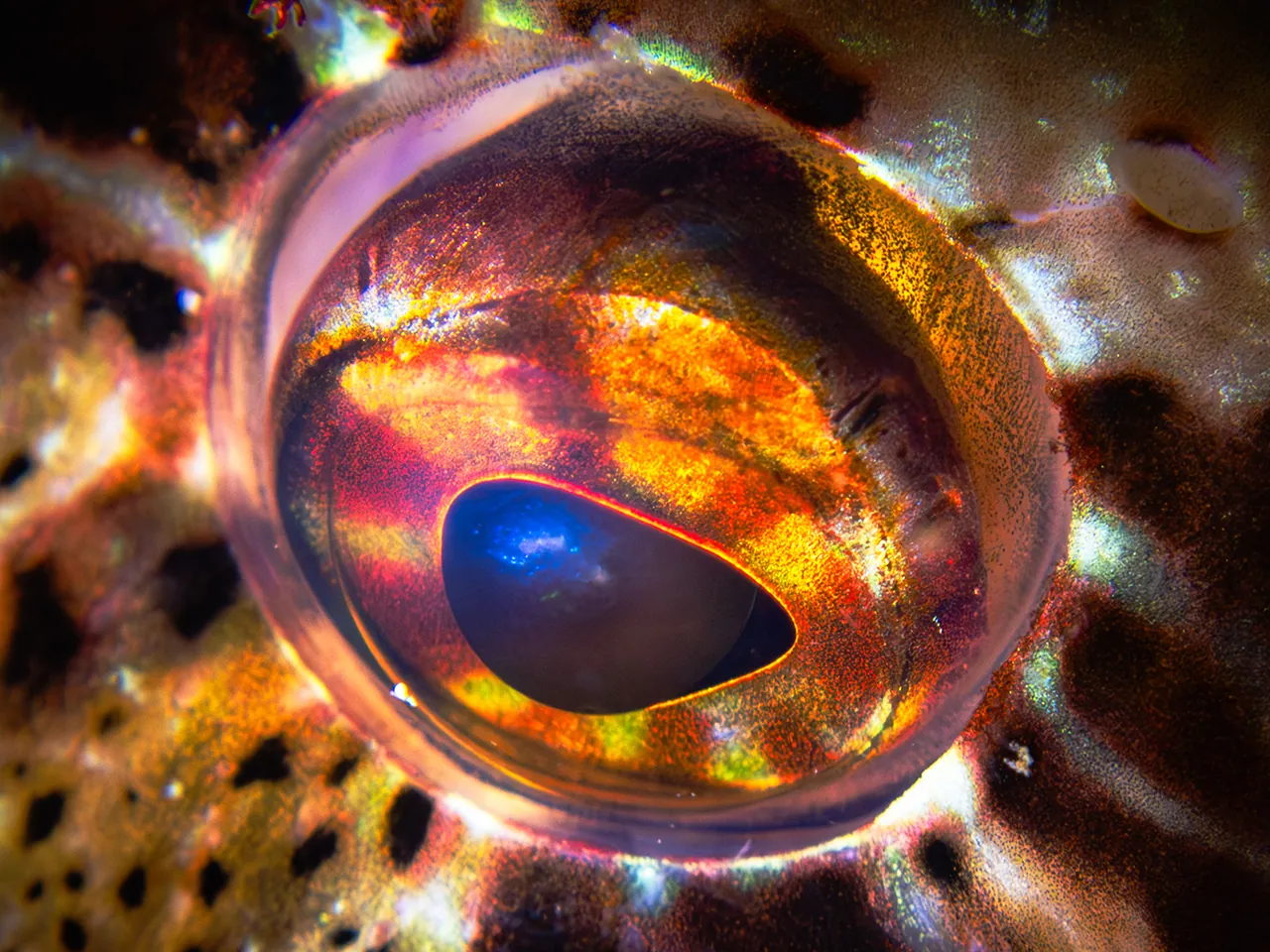

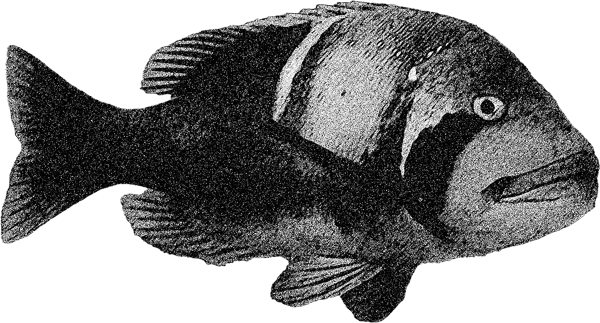

#0042 Red roman – Chrysoblephus laticeps

Large and bright red or orange, this iconic species is beloved by underwater photographers and, sadly, anglers and spearfishers. Females tend to hang out in groups, while territorial males patrol their patch. A remarkable feature of these attractive fish is their ability to change sex from female to male when females reach maturity at about 17-20cm and change to becoming males at 30cm length. When populations are over-exploited, this process is accelerated, with the sex change occurring at a smaller size. Crustaceans, worms, echinoderms and mollucs ensure this hefty species remains fed – Red romans are expert predators, ambushing their prey rather than stalking them. We always love having Red romans around us on our dives!

@saveourseasfoundation #seachangeproject #1001species #1001speciesproject #biodiversity

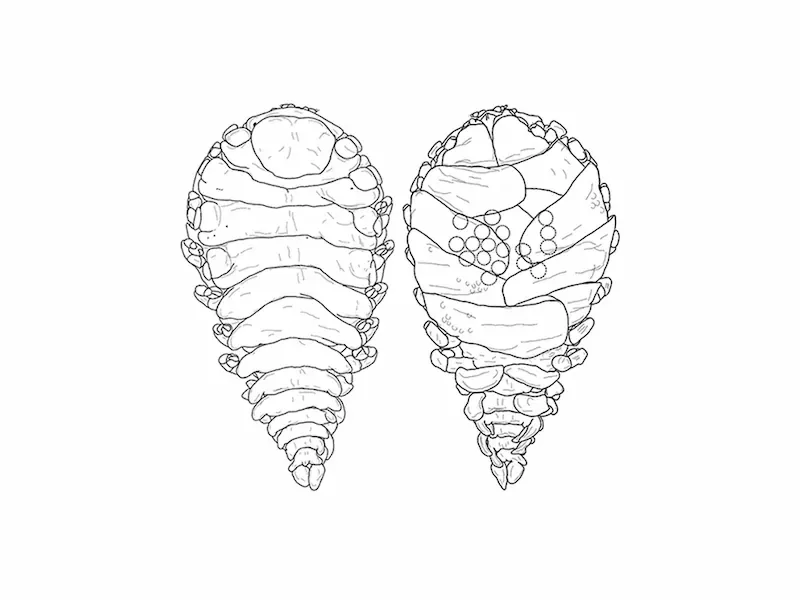

#0041 Reticulated kelp-louse – Paridotea reticulata

Adaptative mechanisms take various forms in marine animals, and this large isopod has been specially equipped to ward off chemical warfare. The gut of these green- to brown-hued louses contain surfactants (think the compound in washing detergent that stirs up activity on the surface you are cleaning to help trap dirt and remove it from the surface), which enables them to stay unaffected by chemicals released by its staple food: kelp. Added to this is a chitinous lining, a semi-permeable layer that prevents the kelp chemicals from penetrating the body. A less complicated food source is the occasional dead fish, scavenged from gill nets. Reticulated kelp-louses have several smaller cousins in the region and are distinguished by pointed tips of the posterior body section, which also provide protection.

@saveourseasfoundation #saveourseasfoundation #1001seaforestspecies #1001species #1001speciesproject

#0040 Scaly horse-mussel – Atrina squamifera

Out of thread for your holiday sewing project? Like their Mediterranean cousins, perhaps the Scaly horse-mussel could help. Those dark, hair-like ‘tails’ seen in the second image are called byssal threads, and their job is to anchor the shell to small gravel and objects in the sediment and create a sand-anchorage. Greek mythology tells us that the threads of horse-mussles were woven into the hardy cloth that served as Jason’s golden fleece – which is just incredible and symbolises royal authority, power and divine blessings. Large, fragile and golden-brown, our local Scaly horse-mussel has external scale-like cusps that run longitudinally down the shell, which is hinged by an elongate ligament. They live partially buried in sand, their large and gaping posterior poking out into the water, which provides food particles that are filtered through enlarged sieve-like gills. This striking species is generous with its body: its shell is often packed with fouling organisms, which use it as a convenient ‘island’ and serves as a home for many marine species. Horse mussels are globally threatened and we are lucky in South Africa to still have healthy populations!

@saveourseasfoundation #1001species #1001speciesproject #seachangeproject #greatafricanseaforest #marinebiology #horsemussel #biodiversity

#0039 Pink meanie – Drymonema sp.

Observing a rare animal in the seaforest gets us crazy-excited. The Pink meanie, which belongs to a small and recently created family that contains just a single genus, is one such species. This beautiful, rarely seen jellyfish is a rosy-pink hue and has a distinct fairly flat umbrella, numerous layers of petticoat-like oral arms, and long trailing tentacles. But don’t be fooled by all that prettiness. As the name suggests, Pink meanies voraciously prey on other jellyfish (see image 2), which is thought to keep populations in check. Not much is known about this species that is still scientifically undescribed, and we’re always on the lookout for them as they move through the seaforest, the flattish disc alternating between convex and concave as they pulse in the kelp.

@saveourseasfoundation #seachangeproject #1001species #1001speciesproject #marinebiology #greatafricanseaforest #jellyfish #pinkmeanie

#0038 Shaggy sponge crab – Dromidia hirsutissima

Like a holidaying school pupil before the obligatory term-time trim, these small crabs are a shaggy sight, their coiffure made up of long dense fibrous brown, grey or yellow hairs. And, as if that’s not enough coverage, they also often carry a cloak of other ocean dwellers – sponges, ascidians and seaweeds – which protects them (often through added chemical defence) and provides nifty camouflage. One of six species in the endemic genus, five are found in False Bay and the Great African Seaforest. While they are usually nocturnal, Shaggy sponge crabs sometimes venture out during the day, relying on their camouflage to move around undetected.

@saveourseasfoundation #seachangeproject #1001species #1001speciesproject #marinebiology #crab #greatafricanseaforest

#0037 Strap caulerpa – Caulerpa filiformis

They might look like seagrass and sway like seagrass, but these dark-green ‘meadows’ are actually a type of algae. With strap-like fronds that emerge from a smooth white stolon – a creeping horizontal stem – Strap caulerpa grow in the sand with root-like rhizoid anchors that attach to buried rocks in intertidal pools and shallow reefs. They form ecologically important habitat and locally enhance biodiversity, especially of gastropod species. An unusual distinction is that the frond of the Strap caulerpa is one enormous cell containing many nuclei. An easy way to understand this is by imagining a house: usually, it’s divided into lots of little rooms (like cells), each with its own light source. But here, the house is one huge open hall, and instead of one light bulb , there are many lamps around the hall. This species is sometimes confused with seagrass, which is a flowering plant, not an alga. However, like seagrass, it relies on photosynthesis and forms these dense beds that can appear almost luminous in bright sunlight.

@saveourseasfoundation #1001species #1001speciesproject #strapcaulerpa #seachangeproject #marinebiology

#0036 Pink-edge bluebottle – Physalia megalista

Many of us are familiar with blue-hued bluebottles, known for their painful sting. But did you know there are not one but at least two species in the Great African Seaforest, including this pink-tinged one? While its trim colour differentiates it from the familiar blue P. utriculus, other distinguishing features include a strongly crimped sail (the inflated float one sees at the surface) and considerably longer feeding tentacles. Bluebottles are colonial hydrozoans, with each colony male or female. They reproduce by shedding sperm and eggs into the water, forming larvae that drift in the water until a float-forming zooid develops, lifting the colony to the surface. Those formidable tentacles aren’t for malice but for survival: they paralyse small fish and crustaceans, reel them in, and deliver them to feeding zooids for digestion and nutrient sharing across the colony.

#1001project #1001seaforestspecies #1001species @saveourseasfoundation #taxonomy #marinebiology #pinkedgebluebottle #bluebottle

#0035 Ornate amphipod – Cyproidea ornata

Fondly known as the Bumble bee amphipod, these teeny tiny creatures have earned their stripes in warning colouration. Common on shallow reefs, they scuttle boldly in the open, their yellow-and-black bands presumably warning off predators. Bean-shaped bodies, red eyes and striped side plates give them a striking look, despite their tiny size – just 3-4mm, not counting their short antennae. Beloved by macro photographers, they are often tracked as they feed on bryozoans, such as the Rustic lace bryozoan Membranipora rustica, a familiar face from post #0016. Gathered in swarms upon these hosts, Ornate amphipods create a buzz of ‘bumblebees’ riding out mealtime together. 🎬 Swipe to see this in action.

Image and video: @jannes_landschoff

@saveourseasfoundation #1001project #1001seaforestspecies #1001species #greatafricanseaforest #seachangeproject #saveourseasfoundation #marinebiology #amphipods

TEAM

1001 Seaforest Species is a multifaceted project with ambitious goals, made possible through the hard work, support, and collaboration of many valued contributors

Dr Jannes Landschoff

Jannes is a marine biologist, trained crustacean specialist and ecologist who leads the scientific research for 1001. His interests and talents in the field of natural history span from documentary photography and film to ecological biodiversity research and conservation. He is a Research Fellow at the Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University.

Craig Foster

Craig has spent more than a decade practising underwater tracking in the Great African Seaforest. He brings these skills to the project by closely observing the ways of the 1001 species, learning from them, and then using his storytelling background to weave rich tales about their often secret lives.

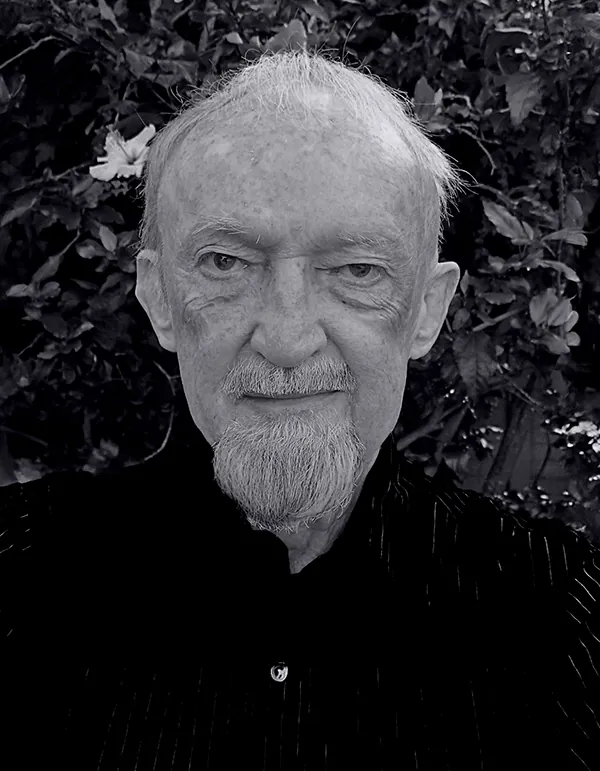

Emer Prof. Charles Griffiths

Emeritus Prof Charles Griffiths is a former Head of the Zoology Department and Director of the Marine Biology Research Institute at University of Cape Town. He has been studying the marine fauna of the region for over 50 years and has described over 100 species new to science. He is author of several guide books to regional fauna and produces a YouTube channel, Explore the Shore ,with his son Matthew. He wrote many of the 1001 Seaforest Species pages.

TRACKING ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Craig would like to acknowledge his original tracking mentors — !Nqate Xqamxebe, Karoha Langwane, and Xlhoase Xlhokhne — who inspired his journey into underwater tracking. This technique, shared with Jannes and the Sea Change team, continues to evolve, has led to numerous scientific discoveries and strongly influences the project, for which we are deeply grateful. We also extend our thanks to master tracker JJ Minye for his invaluable contributions to our intertidal and coastal tracking practices.

!Nqate Xgamxebe

Karoha Langwane

Xlhoase Xlhokhne

JJ Minye

Principal Partners

Over the years we’ve had the privilege to come to know and work with many of the deeply passionate team from the Save our Seas Foundation (SOSF) – our 1001 Seaforest Species principal collaborator and funder. SOSF have spent over 20 years protecting sharks and rays around the world. We feel very grateful to work with this fabulous team of scientists and storytellers, together giving voice to the countless voiceless animals that are our teachers, our inspiration and our life support system.

Red Roman

The Red roman is one of the kelp forest’s most iconic fish, known for its curiosity towards divers. These fish start life as females in small groups but, at around 30 cm, transform into males and become territorial over a specific area. In protected environments, they can live for at least 17 years, becoming like kin to those of us who dive there regularly. This large male Red Roman followed us closely on one of our swims, adding to the feeling of being at home in the seaforest.

Media

Recent Articles

New discoveries: three tiny species added to South Africa’s spectacular marine life